I promise that I will end this series of posts with some actionable conclusions. I thought this would be a Point A to Point C series, but it’s turning into a Point A to Point E series. The final post in this series will be my expectation of how home prices and construction activity will respond in the coming recession.

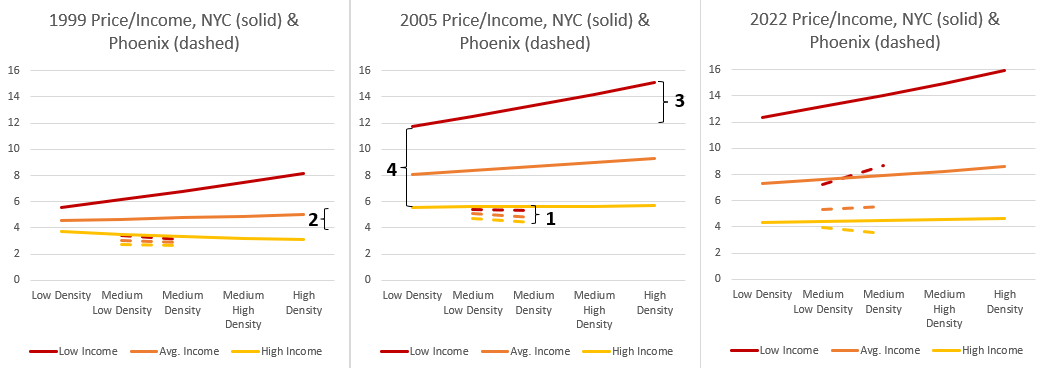

In this post, I am going to describe the various factors that make housing more expensive in a given city. Figure 1 will be the visual guide for this discussion. It shows the price/income level in New York City and in Phoenix at different income levels and density levels in three different years. (I have also used a property tax control variable.)

In the chart, Phoenix is represented by the dashed lines while New York City is represented by the solid lines.

We Made Cities Illegal

The first thing you might notice is that New York City has much more variation in density - both lower and higher.1 On the one hand, New York has very strict density limits in some exurban areas that Western cities don’t share. On the other hand, it became a city before zoning and before the automobile, so there is much more density there.

Cities across the country made that level of density illegal during the 20th century. Even New York City did, but it had so much dense housing that there remains quite a bit of it even after much of it has been cleared out. The densest parts of it have declined since the 1930s. To the extent that the city has continued to grow, the less dense areas have had to make up for the decline in the densest parts.

Queens has grown. Brooklyn and the Bronx have been roughly flat over the last century or so. Manhattan has significantly shrunk.

As I have discussed before, the data from New York City housing makes it clear - residential density is an inferior good. Poorer families are willing to pay more for it. In the aggregate, richer families are not. Richer families prefer exclusion. One thing they prefer is not living near poorer families.

The red solid lines (poor ZIP codes) slope up in all years (poor families pay more for dense neighbourhoods), and the solid yellow lines (rich ZIP codes) are level or downward sloping (rich families don’t pay more for dense neighbourhoods).

The signals these preferences give depends on how you look at it. Price/income, price/rent, price/acre, price/square foot, etc. All of these measures convey different information. I generally look at price/income because that is the margin on which the peculiar condition of the American housing shortage is most clearly highlighted.

When cities were built for everyone, the Lower East Side and the Upper East Side of Manhattan were very different places. I’m not sure they differed that much on a price/acre, price/rent, or price/square foot basis. Sections of them might have even had similar infrastructure. Comparing two buildings with similar acreage and square footage, the one on the Upper East side might have housed 100 people while the one on the Lower East Side housed 1,000.

Builders on the Upper East Side served the preferences of rich residents by building large units that would be too expensive for poorer residents. Builders in the Lower East Side served the preferences of poorer residents by building a lot of affordable units in a small area so that they were affordable and came packaged with a lot of neighbourhood amenities.

I suspect that there was a price/income gradient in the past, as there is now. The prices of units in the Lower East Side were much lower, but the price/income was probably higher than in the Upper East Side.

Residents of the richer neighbourhoods paid for lower density, and residents of the poorer neighborhoods paid for more.

Thoughts on Filtering

As I think about this, I am afraid I must question one of my main points about housing.

I frequently criticize the current literature when there are conclusions that supply conditions don’t matter. That is based on analyzing our current market, where the mortgage crackdown has temporarily made supply similarly inelastic in every city. Because they have not grappled with the fundamental shock that defines our current market, they are treating an anomaly as if it is a state of nature.

I may be doing something similar when I claim that housing affordability is all about filtering. If the densest neighborhoods in classic cities were the poorest, then it seems unlikely that it resulted from filtering. I suppose that large buildings with large units could over time be subdivided into smaller units, leading to more density within the original infrastructure. But, in many cases, the very dense and affordable housing was built for that purpose.

I realize as I think through this, that housing affordability is only “all about filtering” because we have universally made purpose-built dense affordable housing, like the neighborhoods immigrants lived in in Manhattan, illegal.

There is the surface-level sense in which zoning and anti-housing local obstructionism are anti-poor. People generally don’t want their neighborhood to fill up with residents that are clearly of a lower socio-economic status. They make this very clear at the community outreach meetings that most multi-family housing projects have to go through.

It’s basically a form of statistical discrimination. It’s not an unreasonable concern. The problem is that in the process of addressing that concern, we have dived head-first into a collective action problem where every city makes sure that its communal infrastructure is purposefully designed not to serve poorer families.

We have backed into a collective norm where we have made city-building illegal precisely because cities are valuable for our most economic vulnerable residents. When we built cities, poor people flocked to vibrant centers.

There were a lot of problems with those places! Those problems were an important reason why we tore so many of them down.

But since we eliminated them, we eliminated the primary way in which cities served poor families. Now, poor families live in the leftover places - the parts of town that were designed to exclude them, but that over time were abandoned by the families that they were built for. Now, poor families largely live in the carcasses of dead neighborhoods that were originally built to exclude them.

Obviously, filtering has been and will have to be an important element in reattaining affordable housing in the US. But, most cities look much like Phoenix does in Figure 1. They don’t have vestigial density and they legislated away their ability to create it. Any equitable solutions to the American housing crisis will at best be half-measures until the zoning Albatross has been removed from our necks.

Affordability Vs. City-Building

I write a lot about the mortgage shock and its effect on affordability. That’s because in most of the country, it is the main cause of the shortage of units, and the shortage of units is the main reason for the affordability crisis.

The issue with the current affordability crisis is that families don’t get anything for their expense . They are paying more for worse housing, and the less they are able to pay, the more inflated the expenses have become.

The zoning crisis, on the other hand, isn’t an affordability crisis. It’s a quality of life crisis. Poor families in the densest parts of New York City pay more than poor families in Phoenix do because those dense neighborhoods provide value to them . Poor families would pay more for houses in Phoenix if we allowed developers to build the types of neighborhoods that serve poor families well in New York City.

Mark number 4 in Figure 1 is what poor New York families have to pay because there isn’t enough housing. Mark number 3 is what poor New York families pay for housing because it was built for them .

These are two different issues that happen to have some overlap. City-building and housing affordability. I write about housing affordability because I’m an idiot-savant. My skill is seeing things that any idiot can see, and for some reason I don’t fully understand, occasionally, it takes a special kind of idiot to see them.

So, I write about affordability because the causes are big and easy to see - the mortgage crackdown was piled on top of our unwillingness to permit apartments.

The city-building problem is above my skill level. So, I don’t write about it as much. Cities are endlessly complicated. There are countless good and bad things that happen there.

For approximately 9,000 years, people have moved to cities because the positives outweigh the negatives.

In the last century, we tried to get rid of the negatives by getting rid of cities. Where poor families congregate, things will frequently get rough. We initially tried to solve this by bulldozing those neighborhoods as part of “urban renewal” and not replacing them with anything. Now, we have devolved to bulldozing tent rows. This obviously isn’t the solution.

The solution for a developed 21st century society is to keep building cities where everyone can thrive and to provide generous public services in the poorer neighborhoods and high levels of support for public safety.

I don’t have the slightest clue how to negotiate that process across the geography of a city. I’m leaving that hard work for the urbanists. The point of this post is to explain why in the next post, when I write about the construction industry, I’m dumping all the complicated stuff. I’m taking the lazy way out.

“Where does the value of this house come from?” is a very complicated question in a city. Too complicated for an idiot(-savant) to analyze. But, in 21st-century America, we currently generally only have a construction industry where cities are illegal, so I can limit my discussion in that post to simple places like Phoenix. It’s easy to analyze where the value for every home comes from in cities where the complicated sources of value have been avoided.

The Four Sources of Urban Home Values

So, with all that being said, let’s walk through Figure 1 to compare the various factors that lead to higher housing costs. They are listed here from least to most important in New York City today.

-

Agglomeration value

-

Cyclical inflation

-

Density

-

Supply Shortage

1. Agglomeration Value

Mark 1 in Figure 1 is where we might estimate agglomeration value - the value of being in a big, vibrant city with lots of specialized and skilled workers and industries. The difference between what rich families spend in New York City compared to Phoenix is a partial estimate of agglomeration value.

There are many aspects of agglomeration value not captured by Mark 1. Phoenix has agglomeration value. Millions of people have moved there over the past century for that reason. Since Phoenix didn’t lack housing until 2008, the agglomeration value had little effect on home prices. It all went to consumer surplus. Also, rich households can adjust to the higher cost of New York City housing by trading down - smaller units, longer commutes, etc. So, agglomeration value isn’t fully captured by looking at price/income ratios.

As I said, I’m taking the lazy route. From here on out, I’m writing about affordability, not city-building or quality of life. Agglomeration value could be out of this world. It could specifically be out of this world in New York City. But, our housing affordability crisis is well defined by the problem of housing costs and home prices outpacing incomes, and on that margin, agglomeration economies are small potatoes.

The lowest price/income ratio in rich ZIP codes has ranged from about 10% to 60% higher in New York City than in Phoenix, and the average income is about 10% higher in New York City. There is substantial evidence of agglomeration value in New York City, or at least of agglomeration value that creates income for landowners rather than workers, corporations, or consumers.

2. Cyclical Inflation

From 1999 to 2005, price/income ratios increased by about 60-70% in all parts of Phoenix and in the richest parts of New York City. That’s a lot! It was a big cycle.

There are various facets to this. Local growth, macro-level changes in housing markets, mortgage access, interest rates, etc. I generally push back against ascribing too much importance to interest rates, but I think the most likely way that they influence home prices is because land value is sensitive to them more than the value of structures is. That land value could be from location, from scarcity, or from amenities. Real long-term interest rates declined from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s. This appears to have been associated with rising home values in the most constrained cities like New York, and it was associated with rising prices across the metro area, in rich and poor neighborhoods (more on this in an upcoming paper).

The Erdmann Housing Tracker currently shows markets pretty cyclically neutral, but in Figure 1, prices in the rich ZIP codes have not fully reverted to the 1999 levels. Long-term real interest rates are about the same as they were in 2005, but they are still a point or two less than they were in 1999.

Price/income ratios in rich ZIP codes in Phoenix were about 2.7x in 1999 and they are about a point higher now. Price/income ratios are about a point higher, on average, in the rich ZIP codes of New York City, too. Maybe 1999 was a bit cyclically negative. I think it’s plausible that much of the shift noted by Mark 2 is related to interest rates pushing land values higher from the mid-1990s to about 2002. (One way to prevent that is to allow adequate construction so that land values remain a small part of the total cost of housing.)

3. Density

Density value only applies to New York City and a few other cities, like Chicago. In New York City, price/income ratios in high density poor ZIP codes have been about 2.5-3.5 points higher than in low density poor ZIP codes.

I think we can infer that if we could push our gaze back just a bit earlier in time, we would have found that the price/income ratio in the richest New York neighborhoods tended to be around 4x or a little less. In the low density poor ZIP codes, they were probably 4x-5x. And, in the high density poor neighborhoods, it was likely around 7x or a little higher. Probably a bit more than a 50% premium.

The premium now is more like an additional 3.5 points, but that is smaller in percentage terms because the scarcity problem has pushed prices so much higher for all poor ZIP codes.

In all three of of these categories, these are not small effects. They can be quite sizeable! They are important enough to demand attention, analysis, and conversation. But they are all dwarfed by the scale of the supply shortage. And, they all reflect some form of actual value, whereas the supply shortage is simply a loss of real incomes. On the affordability question, scarcity is the issue.

A neutral city might have price/income ratios around 3x across the city. Maxing out density value, cyclical value, and agglomeration value, New York City price/income ratios might range from 6x in rich neighborhoods to 9x in dense poor neighborhoods.

In 2022, low density poor neighborhoods in New York City sell for 12x income, and that is almost all from scarcity.

4. Supply Shortage

The supply shortage was already sizeable in New York City by 2005. Today Phoenix also has a sizeable supply shortage.

In New York City, that means that poor ZIP codes pay triple the price/income ratio that rich ZIP codes do, even where they aren’t paying a density premium.

In Phoenix, there was little difference between poor and rich ZIP codes before 2008. Today the poor ZIP codes pay about double the price/income as rich ZIP codes.

In 2022, there appears to be some signal of density value in Phoenix. Phoenix has taken some small steps toward city-building. There is now an extensive light-rail line, and there are a growing number of young households in the denser parts of Tempe and Phoenix who are now living without cars. Could Phoenix be becoming a city? Or is this just some noise in the data related to large recent shifts in prices?

Could we hope that Phoenix is becoming a place with some Medium High Density ZIP codes, where poor families pay 5x or 6x their incomes for homes because the city has value for them instead of paying 8x because the city has made it a point to avoid supplying what they need? That’s the opportunity before us.

Conclusion

In the next post(s), I will look at a simple market, a market like Phoenix and every other American city with a significant construction industry, and because it is so simple, I might be able to add a couple of fresh complications to understand why homes there are selling for what they are, and why we are (or aren’t) building them. And, what might happen on those margins as the economy softens.

***

Technically, the 5 density categories represent ZIP codes with residences per square mile of 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10, on a natural log scale. Phoenix has no ZIP codes in this data set with log density of 6, 9, or 10. The income categories are the ZIP code with average log income equal to the metro area average, and ZIP codes with incomes 1 point above and below that, on a natural log scale. They are modeled as if the average property tax is 1% of market value in all ZIP codes.

Original Post