Once the stuff of science fiction, space tourism is fast becoming a reality—reserved for few, watched by millions, and sparking profound questions about the future of our planet.

Introduction

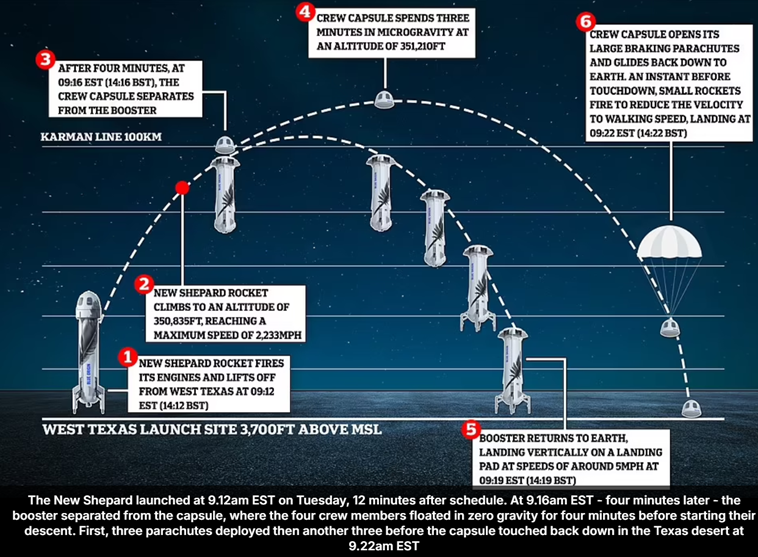

Last week, history was made as Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket launched its first all‑female crew into suborbital space. For roughly eleven minutes, six influential women— pop icon Katy Perry, CBS anchor Gayle King, aerospace engineer Aisha Bowe, civil rights advocate Amanda Nguyen, film producer Kerianne Flynn, and mission leader Lauren Sánchez— soared above Earth’s surface. They glimpsed the planet’s curve, floated in zero gravity, and were serenaded by Katy Perry singing “What a Wonderful World.” With no pilot on board, this fully autonomous mission marks a striking milestone in commercial spaceflight. But are we any closer to making space tourism a commercial reality?

Key Players

The dream of sending civilians, not just astronauts, into space has been floating around for decades. The reality began in April 2001, when American businessman and engineer Dennis Tito became the first private individual to travel to space. His journey was arranged through a deal between the US company Space Adventures in partnership with Russia’s MirCorp. Initially set to visit the aging Mir space station, Tito’s plans were redirected to the International Space Station (ISS) after Mir was decommissioned. He paid a reported $20 million for the trip aboard the Soyuz TM-32 spacecraft and spent seven days in orbit, making history as the world’s first space tourist.

Now, more than two decades later, the space tourism industry is gaining momentum. A new space race is underway—this time, driven not by nations, but by private companies vying for a foothold beyond Earth’s atmosphere. Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN ), established Blue Origin, responsible for the headline mission of the all-female crew, in 2000 with a long-term vision of enabling millions of people to live and work in space. The goal was to develop cost-efficient rockets that could alleviate heavy industry off Earth. For nearly twenty years, Blue Origin operated mostly out of the spotlight. It wasn’t until 2015 that the company carried out its first rocket launch, with an uncrewed test flight of the suborbital New Shepard vehicle. In July 2021, Bezos himself joined the first passenger flight aboard New Shepard, becoming the first billionaire to cross the Kármán line, considered as the edge of space. Since then, the fully reusable New Shepard rocket has completed eleven crewed missions, flying 58 civilians into space.

In terms of numbers, Virgin Galactic stands out as the leader in commercial space launches. Founded by Richard Branson in 2004, the company went through years of testing and delays before finally completing its first fully crewed flight in 2021. Since then, its spaceplane VSS Unity has carried over 65 people to the edge of space, around two-thirds of them being paid passengers.

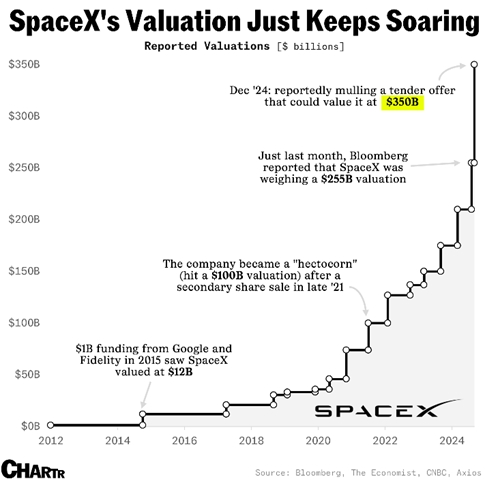

The world’s leading rocket-launch provider is SpaceX, a space venture founded by Tesla (NASDAQ:

TSLA

) CEO Elon Musk, valued at 350 billion dollars. The company has been behind some of the most impressive achievements in modern space exploration. Unlike its competitors focused on short suborbital trips, SpaceX designs its rockets for full orbital missions, capable of travelling much farther and staying in space for longer journeys.

Space Perspective, another space tourism company, offers a more luxurious approach to space travel. Instead of rockets, it plans to carry passengers to the edge of space using a high-altitude balloon and a pressurised capsule. The experience is slower and smoother, ideal for those seeking panoramic views rather than adrenaline rushes. Flights are expected to begin this year, with tickets priced at around $125,000.

In China, Deep Blue Aerospace is an emerging contender aiming to join the suborbital tourism race. The startup is developing its reusable Nebula‑1 VTVL rocket and crew capsule, and announced in October, a roadmap to begin suborbital passenger flights in 2027. Tickets are priced at roughly ¥1.5 million (about $210,000), and Deep Blue even presold two seats via an Alibaba (NYSE: BABA ) Taobao livestream at a discounted rate of ¥1 million each.

Business Model

Space tourism is a niche segment of the aviation industry. It is defined as the commercial activity of travelling into space for leisure rather than scientific or professional purposes. Unlike traditional airlines or cruise ships, it remains a nascent industry with no established profit models or decades of operational experience to guide the industry. There are currently two main types of space tourism: suborbital flights, which briefly cross the Kármán line (100 km altitude) and offer a few minutes of weightlessness; and orbital missions, which involve longer stays and often include docking with the ISS or private stations. Lunar tourism, which involves private missions around or to the Moon, is still in early development, with projects like SpaceX’s DearMoon (planned for this year) and Blue Origin’s Blue Moon aiming to make it a reality.

The revenue model is built on astronomically high-ticket prices, suborbital flights range from $250,000 to $450,000, and orbital missions, such as those aboard SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsule, cost around $55 million per passenger. As such, space tourism remains accessible only to a tiny, ultra-wealthy segment, making it a billionaire’s hobby.

Developing the technology behind these experiences requires substantial investments in research and infrastructure, with early funding coming almost entirely from private investors or the founders themselves. Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Richard Branson have each invested personal fortunes to fuel their space ambitions; Bezos admitted in 2017 to sell Amazon stock to fund Blue Origin. The long-term hope is that reusable rockets will eventually bring down costs. When Apollo 11 first brought humans to the Moon, only the command module made it back to Earth, most of the spacecraft was left behind. Blue Origin is among the aerospace companies aiming to change that. Its system is designed for maximum reusability, with nearly 99% of the vehicle’s dry mass, including the booster, capsule, engine, landing gear, ring fin, and parachutes, used again after each flight. By flying the same boosters multiple times, companies aim to spread out expenses and make space tourism slightly more affordable in the future.

Financial and technical challenges aren’t the only hurdles. The industry also faces complex regulatory and insurance requirements. Every passenger flight must undergo strict safety assessments, environmental reviews, and meet extensive liability coverage obligations. Insurance premiums alone can reach tens of millions of dollars per launch. Under US law, all spaceflight participants must complete tailored training programs based on their mission profiles. For example, Blue Origin prepared its New Shepard passengers over a two-day program that includes physical conditioning, emergency protocols, and instruction on safety systems and zero-gravity procedures. Companies must also account for possible delays, cancellations, or even mission failures, all of which require contingency planning and compliance with aviation and spaceflight authorities.

According to Research and Markets, the global space tourism market was valued at USD 1.23 billion in 2024, and is expected to grow at a CAGR of 31.6% from 2024 to 2030. This rapid growth is fuelled by the rising public interest in commercial space travel, increased investment from private companies and high-net-worth individuals, and technological advancements in reusable launch systems and spacecraft design. Innovations in radiation protection, life support systems, virtual and augmented reality simulations, as well as improvements in spacecraft safety and passenger comfort, are improving the sector’s long-term commercial viability.

Concerns

As exciting as space tourism sounds, many argue it is an ultra-exclusive experience, more of a playground for billionaires than a step toward truly accessible space travel. Others question its purpose, pointing out that unlike research missions run by NASA or ESA, most tourist flights don’t contribute much, if anything, to science. The environmental impact is another growing concern. Rockets release gases and particles high into the atmosphere, where their effects can be longer-lasting and more damaging than emissions on the ground. It is estimated that Virgin Galactic produces approximately 12 kg of CO₂ emissions per passenger per mile, compared to around 0.2 kg of CO₂ per passenger per mile on a commercial aircraft flight. Blue Origin claims that its New Shepard rocket produces only water vapour, with no carbon emissions— but experts aren’t convinced. Professor Eloise Marais, an atmospheric chemist at University College London, warns that water vapour itself is a greenhouse gas, and at that altitude, it can damage the ozone layer and form clouds that trap heat. Additionally, other non-CO₂ emissions like nitrogen oxides, contribute to global warming.

Then there’s the issue of safety. Unlike established space agencies with decades of experience, private companies are racing to prove themselves in a competitive, high-pressure environment. This urgency can mean faster timelines, less testing, and higher risk. Experts warn that even short visits to space can affect the human body, causing radiation exposure, and other health concerns.

Conclusion

The space tourism industry remains in its early stages, more a symbol of technological ambition and elite adventure than a mainstream mode of travel. Every successful launch is a meaningful step towards proving that short commercial missions can be executed safely. But if reusable technology advances, regulations evolve, and costs begin to drop, the door may slowly open for a broader public.

For the few who have made the journey, seeing Earth from above is often described as life-changing: a fragile blue sphere, floating in the darkness, without borders or divisions. That perspective, known as the “overview effect,” reminds us just how precious and delicate our planet really is.