In the previous post, I discussed a new paper from Edward Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko. It seems to me that economists are putting effort into testing relatively weak hypotheses about trends in housing because of an apparent complete and universal ignorance about the sharp shift in mortgage access in 2008.

Tyler Cowen linked to the paper and added this comment: “The suburbs again are underrated. I am all for the various urban YIMBY ideas I hear, but keeping growth-viable suburbs up and running may be more important.”

This is true, in the immediate future, and the Glaeser and Gyourko paper is a nice documentation of how much of the housing shortage has been about the death of suburban expansion. The recovery of the suburbs would benefit from reactivating 20th-century lending norms.

Meanwhile, John Cochrane wrote in the Wall Street Journal (emphasis mine):

The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 and other laws and regulations were supposed to curb the GSEs’ influence and allow a more vibrant private market to emerge. Instead, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, which oversees Fannie and Freddie, raised loan limits, loosened credit standards , and expanded programs such as first-time home-buyer incentives and special refinancing options….This river of subsidy should at least make homes more affordable. But it doesn’t. Subsidizing demand in the face of supply restrictions sends prices up. House prices are higher than ever, with the median home up nearly 40% since 2020.

A deep retraction of mortgage credit cut suburban housing construction by 50% for a decade, so deeply that excess rent inflation has run, frequently, 2% or more than general inflation. Cochrane thinks the problem is too many federal subsidies for home buyers. Glaeser and Gyourko are reaching around the elephant in the room, but at least they are in the room!

There are 3 ways to end the American housing crisis. (1) Allow cities to adequately construct multi-family and infill housing. (2) Return to 20th-century lending standards. Or (3) Allow the new single-family build-to-rent segment to grow.

Actually, there is a fourth way. Give American families 2 or 3 generations to adjust to the 2008 hit to housing supply from the mortgage crackdown. Millions will need to be regionally displaced from the coastal metropolises. Millions will need to accept a lower level of amenities, smaller homes, etc. And rents will be elevated for a few generations while those difficult transitions are made.

Also, everyone is going to be pissed off at landlords, immigrants, families with more incomes, the homeless, etc. while the transition happens. Americans will internalize a toxic Malthusian ethic where wealth and income are fixed, so that everyone who gets more is an enemy to someone who must have less. Sounds fun, doesn’t it?

After a decade of it, we’ve got ICE throwing tear gas in LA. Ask why hardworking, honest immigrants need to be rounded up and shipped away, and housing costs are bound to be mentioned. Ask leftists in San Francisco how it could possibly be bad that corporations create high-paying jobs, and the reason will be housing costs .

Anyway, there is a battle over #1 now. The Klein/Thompson book “Abundance” has been a great addition to the rhetoric over that battle. As I highlighted in the previous post , they have received a lot pushback from progressives. Progressives are deeply mired in the fixed-pie Malthusian toxin.

Number 2 is a non-starter. The most devastating policy shift in generations left massive scars across American housing markets, and market-friendly economists can’t get pulled away from the hallucinations of their fever dreams of easy credit to even notice it. They’re chasing heffalumps and woozles, and they’ve just, frighteningly, come upon an additional set of footprints.

That leaves us with #3. Progressive suburbanites are upset that corporations are buying up neighborhoods, and reactionary suburbanites are upset that renters are moving into the suburbs. And, until we universally recognize the centrality of the mortgage crackdown, the exclusionists and enemies of the future are going to win the final battle. Enemies of landlords and enemies of renters find common cause. It’s a sort of Baptist and Bootlegger game, on the darkest timeline.

There are no other battles left to fight. Until #1 or #2 are fixed, without suburban rentals, tents, and overpasses are the next best option.

Glaeser and Gyourko have so many things right. Local land use rules prevent city-building that had previously been a central feature of human development and growth for millennia. Literally. Here is an aerial image of the Sumerian city of Ur, dating to the 4th century BC. As the social app joke goes, “Unfortunately, this sort of dense, walkable neighborhood would be illegal to build in every part of the US today.”

They note that while construction costs have risen, it can’t explain more than a fraction of the rise in housing costs.

They note that inelastic supply has been a problem in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston for a few decades, and it has only spread across the nation recently. They suggest that supply barriers have blocked something like 15 million units, which is in the same range that I would put it.

This is one of the most important political problems for the United States to address going forward. But unfortunately, in 2008, we created a larger problem - a mortgage crackdown.

In fact, I would argue that the vast majority of the 15 million units we need were created by the mortgage crackdown. Before the mortgage crackdown, homes had to be built in places that required painful regional displacement of families. But, they were built.

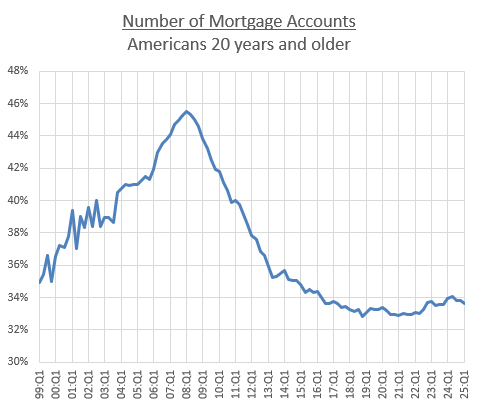

Homeownership actually peaked in the US in early 2004. There was a brief spike in privately securitized non-prime mortgages from 2004 to 2007. The New York Fed shows significant growth in mortgages during that period, in spite of a declining homeownership rate.

A lot of those mortgages were used by small-scale investors and speculators, many of whom were approved based on erroneous, carelessly reviewed, or fraudulent applications. Terms on many of them were prone to instability.

Then, in 2008, after all of that had ended, federal regulators leaned on the federal mortgage agencies to sharply curtail lending to borrowers that they had been serving since well before the private securitization boom. The subprime boom had ended, which created a need for some painful adjustments, and then we poured salt in the wound, and we kept pouring until it overflowed into the fields.

Today, the number of mortgage accounts per American adult is about 25% below the peak, and about 15% below the level it was at before the private securitization boom. It would likely be much lower if families couldn’t provide informal and formal support for young borrowers today. Also, some homeowners who owned homes in 2007 have managed to keep them even though they might not be able to qualify for a new mortgage today.

You would run into a lot of objections if you tried to publish a paper in economics about the pre-2008 period without accounting for the rise in mortgages. The post-2007 decline in mortgage accounts is steeper and larger than the pre-2008 rise. Oddly, you can publish to your heart’s content about the post-2007 period without even mentioning mortgage trends.

In fact, if you do mention a sharp and unprecedented drop in mortgage access, you might be met with puzzlement. It is rare to find a paper that mentions it at all. Following convention, Glaeser and Gyourko don’t mention it. Nobody would demand that they need to. Not even a passing comment in a footnote. Nothing. (I suppose, given Cochrane’s comments, it could be worse.)

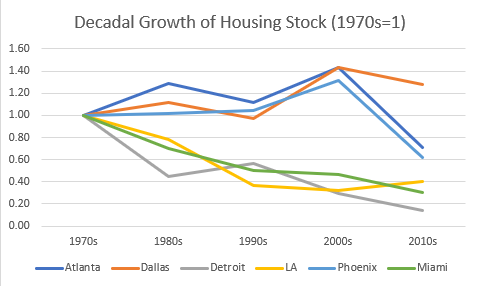

I was playing around with some of the numbers they cite in the body of the paper. They highlight 6 major metropolitan areas in their discussion - Atlanta, Dallas, Detroit, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Miami. In figure 1, using Glaeser and Gyourko’s numbers, I compare the growth of the housing stock of those cities in each decade, relative to the 1970s.

These cities fall into 2 categories - those that kept growing after the 1970s (Atlanta, Dallas, and Phoenix) and those where the housing stock has persistently grown more slowly over time (Detroit, Miami, and Los Angeles). Then, in the 2010s, there was a major, idiosyncratic, downturn in Phoenix and Atlanta.

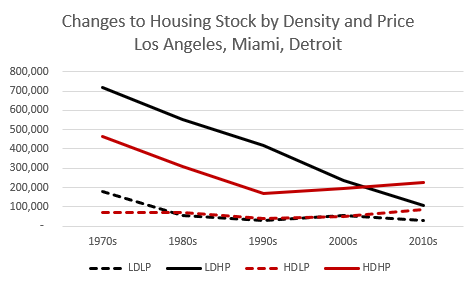

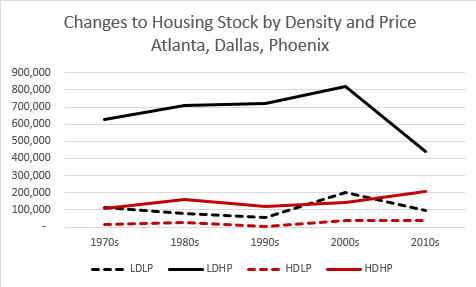

In Figures 3 and 4, I have divided these metro areas between the fast growers and the declining growers. Here, I use Glaeser and Gyourko’s numbers, which they have binned according to density and prices. Low and high density and low and high prices. The 2 categories of metro areas paint a surprisingly distinct picture.

In the cities that have continually grown more slowly over time, the growth has been dependable in the high-priced parts of the region. This is what Glaeser and Gyourko expect to see. New construction should happen in the favored and valuable parts of the city. If this were reversed, it would be a sign that more affluent residents utilize local land use regulations to keep new development from happening in their neighborhoods.

But, Miami and Los Angeles both arguably have reached a stage of development such that geological barriers or state and federal lands set aside as non-developable may be limiting suburban development. Or, in the case of Los Angeles, simply the size of the commuting zone may discourage more affluent residents from moving to the exurban frontier.

They write that, “If existing homeowners in high price areas have become better at controlling land use regulations and stopping new construction, then we should expect to see a decreasing link between high prices and new construction, which is exactly what the data shows.”

But, the shift in the non-growing cities has been more from less dense to more dense than it has been from high priced to low priced. The problem is that as low-density development has declined, high-density development has not risen enough as a substitute. That’s a problem, and it is a problem Glaeser and Gyourko have done a lot of important work highlighting.

High-density areas weren’t growing, whether high-priced or low-priced. Development wasn’t pushed into the lower-priced neighborhoods. It just couldn’t happen anywhere. High-density growth has finally picked up a bit in the last couple of decades, but not nearly enough yet to make up for decades of declining growth in the exurbs.

Figure 4 shows the growing cities. Until 2010, growth of low-density, high-priced areas increased every decade. In the 2000s, growth in low-priced low-density areas kicked a bit higher, but not because growth in the high-priced low-density areas was declining.

All along, these cities may have developed a worse problem than the low-growth cities regarding the blanket obstruction of density that zoning enforces. Growth of dense areas has always been low in the growing cities.

From the 2000s to the 2010s, growth of low-density housing dropped by about 50% in both groups of cities and in both low-priced and high-priced areas. That is because the 50% drop was created by a single, uniform reason - the national mortgage crackdown.

In the growing cities, low-density housing decelerated from the 2000s to the 2010s by about 483,000 units. High-density housing only accelerated by about 62,000 units, barely making up for any of the loss.

In the slow-growing cities, low-density housing decelerated by about 158,000 units, and high-density housing accelerated by about 67,000 units.

There are certainly some margins where suburban housing obstruction surely lowers total production. But, it is at best a distant 3rd here in order of importance. Most importantly, we can’t build cities. No cities across the country, for decades, have been able to grow dense housing of any kind at a rate necessary to provide affordable shelter and to stop regional displacement.

In terms of scale , by far the most important thing that has happened to the American housing supply was the mortgage crackdown in 2008. And because of the most important problem - that density is largely illegal - the big giant new constraint was binding.

The most important issue in the long term is city-building. Density. But to understand that problem properly, we have to appreciate the scale of the mortgage crackdown. In the 2010s, fast-growing cities suddenly needed to find a way to add 15 million new units of infill construction to make up for the lack of funding for suburban expansion. And they were almost perfectly unable to allow anything. Cities of all types. Just entirely incapable of being cities.

Seeing the mortgage problem helps to see the zoning problem so that we can avoid distracting ourselves from what is important.

One final point on demand elasticity.

Glaeser and Gyourko write, “We have not estimated the demand elasticities that would be necessary to know what prices would be if construction rose to 1970s levels, but if the housing stock had grown by the same rate between 2000 and 2020 that it did between 1980 and 2000, then America would have 15 million more housing units.” I’m glad they didn’t try to estimate demand elasticity. I think that would be another distraction.

What the US housing market under the duress of the mortgage crackdown has made clear is that demand elasticity is complicated. Supply is very sticky downward because existing homes are a durable asset that don’t disappear when construction declines.

Demand is sticky downward because families very much dislike trading down to neighborhoods with lower socio-economic status. That’s one reason why there has never been much housing growth in the low-priced neighborhoods in Glaeser and Gyourko’s data. And demand is sticky moving downward to less expensive metropolitan areas because families hate being displaced from family, jobs, friends, etc.

So, prices aren’t that volatile in cities that are growing. When New York and Los Angeles were growing as fast as Dallas grows today, they weren’t particularly expensive. Even if supply isn’t perfectly elastic, families moving to places will happily make compromises. And, if families are moving into a place and they are all making similar compromises, families will very willingly move into a neighborhood in a new city where the average home is 500 square feet smaller if the neighbors are similar in both cities.

Prices only become persistently elevated where supply is so constrained that rising rents are making families poorer. Families don’t want to move away from an entire region where they have personal connections there. And families who are used to living in areas with, say, low crime, are very reluctant to compromise on issues like that to lower housing costs.

I have been coming around to a way of thinking that the regressively rising rents we have seen in the Closed Access cities for decades, and across the country since the mortgage crackdown, are due to that stickiness. They are sort of a friction - a disequilibrium.

It will take years or generations for the transitions to happen. If we don’t solve the problems that are making new construction low, families will very slowly accept things like smaller floorplans relative to what previous generations would have considered normal for a family with a given income.

Currently, rents are rising on individual units faster than incomes are in many cases, and the stickiness in demand means that families aren’t making compromises easily to counteract that. We trade up much more easily than we trade down, and trading up is the general direction of most things in capitalist economies. Eventually, slowly, the houses and neighborhoods will change to facilitate those changes, and slowly, those real adjustments will replace the nominal adjustments that families have been making.

I guess that’s good news. The bad news is that it means that our current conditions are really very, very bad. They have to be to make housing costs so elevated. Total residential real estate value across the country is now inflated about 50% above what it would be under supply conditions anywhere close to normal.

Home prices would not be elevated if supply conditions simply caused real consumption of housing to rise more slowly than incomes do. Under those conditions, Americans would still spend the normal amount on housing, but they would just trade up a bit less. They would live in somewhat less nice homes than they might have.

But, millions of American families are faced perennially with the problem that they would have to lower their real consumption of housing on an absolute basis in order to keep costs from rising uncomfortably. And our demand becomes sticky under those adverse conditions.

That’s why exceedingly high prices before 2008 were generally limited only to a few peculiar cities that perennially had very high rates of domestic outmigration. Those high prices only happen when families are forced to trade down into sticky demand territory.

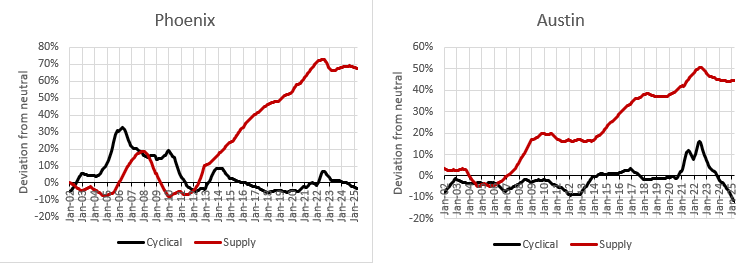

Cities with cyclical booms get a lot of attention, but total real estate value in Arizona or Texas, because of cyclical inflation,n never comes close to the total excess value created by duress.

Figure 5 shows the relative change in the average home value in Phoenix and Austin (using data that Erdmann Housing Tracker “founding” subscribers get) that is related to the sticky downward demand versus the change in home values related to cyclical booms and growth.

This is the average. The downward stickiness is worse for poorer families (though this is the effect on prices, which is higher than the effect it has on rents. In other words, a 1% increase in rents from supply constraints leads to more than a 1% increase in prices).

The mortgage crackdown had to have a massive effect on the production of new homes in order to spread these trends in spending across the country. Small or moderate changes couldn’t have done this. A 50% drop in suburban construction is huge . An immediate loss of 1/3 of the traditional mortgage market is huge . It took a huge effort to make this happen.

Families with above-average incomes are largely exempt from this problem - especially if they are still able to qualify for mortgages, so they are mostly spending a comfortable amount while trading up at a slower pace.

Families with below-average incomes are more likely to be living in homes worth double or more what they used to in order to avoid trading down. If they sell those homes, they are likely to go to all-cash buyers or landlords, but the inevitable explosion of rent inflation that followed the mortgage crackdown makes them valuable.

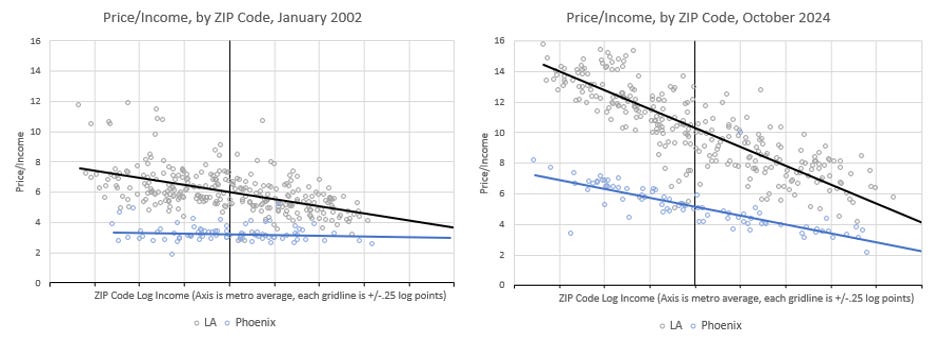

Families with the lowest incomes in Phoenix, Dallas, and Atlanta are now swallowing housing expenses at a scale similar to what families with low incomes in Los Angeles were swallowing in the years before 2008.

But, when they reached their breaking point, those families in Los Angeles did have the option to trade down to a cheaper city when they decided they were willing to accept displacement. Families in Dallas, Phoenix, and Atlanta don’t have that option today because Phoenix, Dallas, and Atlanta were that option, and the mortgage crackdown turned them all into Los Angeles.

Did the poorest neighborhoods in Phoenix and LA discover NIMBYism? Did poor suburbia suddenly create mindblowing amenities? Maybe, via Cochrane, we’re at the tail-end of a 22-year credit bubble! If someone could please get this big gray fleshy thing out of my face, I could figure this out!

I haven’t fully come to a conclusion about how quickly rents might decline if supply returns families to making choices on the trading-up side of the equation instead of the sticky trading-down side.

I think much of the new supply will still come from less dense high-priced areas, but it will increasingly come from single-family built-to-rent housing. As Fishers and Carmel, Indiana have demonstrated, that development might be enough to make Glaeser and Gyourko’s conjecture true. The mortgage crackdown added a new margin on which to exclude, and suburbanites will use it.

Maybe Glaeser and Gyourko are correct, but early. But, again, to understand why they might end up being correct, we have to center the mortgage crackdown in our understanding of the constraints on the market since 2008.

You have to know how important the mortgage crackdown was to understand why the single-family build-to-rent market is growing so quickly that it seems threatening to some communities and to some confused housing advocates. You have to know how important the mortgage crackdown is to understand that zoning constraints didn’t suddenly become more binding in Phoenix and Atlanta.

You have to know how important the mortgage crackdown is to understand how devastating it would be to limit the expansion of single-family rentals.

Original Post