One facet of mortgage data that you normally see cited by credit hawks is that debt-to-income (DTI) ratios are high on new mortgages.

Mortgage originations, especially to borrowers with lower credit scores or lower incomes for homes at lower prices, are a fraction of what they used to be. The average home has much lower leverage than it used to. As a percentage of all buyers, all-cash buyers have been at record highs in recent years.

New homes are increasingly being sold to large-scale institutions instead of mortgaged owner-occupiers. Suburban home construction dropped by 50% in growing cities.

You’d think as this evidence piles up, it would be hard to keep believing that loose lending standards and mortgage subsidies are an important part of the American housing market.

But, we’ll always have DTIs.

I’ve written about this before. One of the surprising early findings I discovered in my review of the Great Recesssion that kept me looking for more information was that, according to the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finance, all of the increase in high DTI mortgages in the pre-2008 credit boom was among families with the highest incomes.

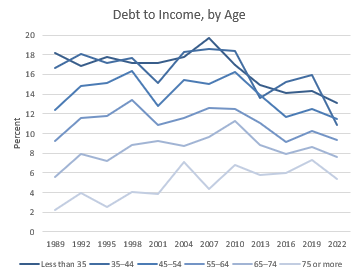

And, high DTIs are mostly a problem created by fixed payment mortgage products with short amortization schedules. As soon as a family takes on a new mortgage, the fixed payment starts to decline compared to their income, the home’s value, the prices of most everything else, etc. By the end of the mortgage, DTIs tend to be half or less of what they were at the beginning. DTIs reported by age reflect this process.

When DTIs are cited, it is based on newly originated mortgages, when DTIs are at their highest.

Before the mortgage crackdown caused such regressive rent inflation, home price/income ratios across most growing cities were relatively similar - typically between 3-4x. They tended to be a little bit higher in neighborhoods with lower incomes, but not much. And homes in poorer neighborhoods tend to have lower price/rent ratios.

In other words, families with lower incomes wouldn’t have to spend that much more on a mortgage to buy the house they live in than families with higher incomes do. But they do tend to spend more to rent the house they live in. So, even if DTIs tend to be a bit higher for poorer borrowers they represent a better deal relative to renting.

For all these reasons, the average DTI on new mortgages hasn’t changed much after 1/3 of the 20th century mortgage market was eliminated.

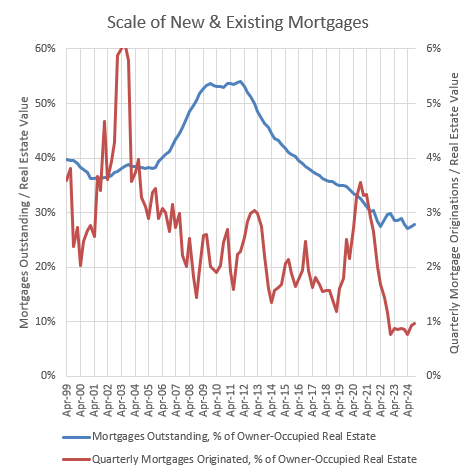

Here’s a way to visualize the importance of these risks. Figure 2 shows the leverage of all owner-occupied homes since 1999 (blue, left) and the quarterly amount of originated mortgages relative to the value of all owner-occupied homes (red, right).

According to AEI, about 45% of new mortgages have DTIs above 43% today, compared to about 25% before 2017.

45% of 1% is less than 25% of 2%. Mortgage access greatly tightened in 2008. It has been tightening again recently. The resulting decline in suburban home construction has raised rents by more than 20% and prices by more than 40%. That makes DTIs higher. In spite of that, the total amount of mortgages originated has declined enough that the absolute amount of mortgages with high DTIs has declined.

Where does this end? If we eliminate high DTI lending, so that mortgages worth only 0.55% of outstanding real estate are originated each quarter, will that finally fix it?

Think about what we’re doing. Rents have been rising faster than inflation, and the less we build, the faster they rise. There is no federal agency preventing you from spending 50% of your income on rent, even though your future rent payments are going to grow like a negatively amortizing mortgage with floating rates.

Mortgage payments are fixed and systematically decline in the future, in real terms. The less we build, the harder it is to get those federal agencies to agree to let you take on those fixed payments. And the fewer mortgages they allow, the less we build.

Mortgage hawks seem to believe that if we do eliminate the last sliver of mortgages still being originated, home prices will then drop by 40%, and American families will then be able to get safe mortgages to buy homes with prices that aren’t inflated.

Why hasn’t dropping mortgage activity to 1% of real estate value done that? Could they be wrong? Could they have spent 40 years misattributing the effects of supply constraints to loose lending and low interest rates?

I, frankly, wouldn’t expect any large number of people communally engaged in a 40-year error to self-correct, no matter the empirical outcome. One difficulty of being human and being in community is that we don’t behave like the physical world. The hotter a pot of water is, the more quickly it will cool down. But for we peculiar humans, sometimes there is a tipping point beyond which being more obviously wrong makes it even harder to self-correct. And, so, the challenge for Americans who need affordable housing again is that much harder, because a lot of economists, experts, and pundits are obviously wrong, and thus unable to correct.

The irony is that the solutions are all in our past. Mortgage norms and land use rules of 30 years ago (or a bit more in some cities) regularly produced affordable housing (the famously flat Case-Shiller chart!). We knew how to do these things.

But, it is also quite possible that instead of rediscovering what we knew, we will end up banning suburban rentals, tightening lending more as rents and prices continue to rise, and fighting over what to do with the encampments accumulating in the parks.

And I don’t know what turns that around. If we end up there, I promise that average DTIs on new mortgages will still be high, and somebody will still be complaining that mortgage subsidies are the reason the tent-campers can’t afford homes.

PS: Here is a paper that finds that the Ability to Repay rule, intended to reduce DTI among other things, and only one of the many regulations put in place after 2008, caused interest rates on affected loans to rise by 10-15 basis points, mortgage originations to fall by 15%, and the allowable leverage on another 20% of affected mortgages to be reduced.

Original Post