The summer months should bring more clarity on how President Donald Trump’s economic policies are affecting the economy. More clarity is what the Fed wants before making further changes to interest rates . The incoming data, including today’s employment report , should be placed in the context of a labor market near maximum employment but with elevated inflation, as well as the forecasts of a modest stagflation this year.

This summer should also provide more clarity on the policies from the White House. The information the Fed receives this month may lead it to begin cutting rates at the end of July, but it’s far more likely that it will want to see the summer’s worth of data before cutting.

Today’s post offers some advice on interpreting the data in the summer of stagflation. There’s a particular focus on how to think about this week’s employment data.

Context Matters

As we receive new data on employment and inflation, it’s important to set them within the context of the recent past and the outlook for the future.

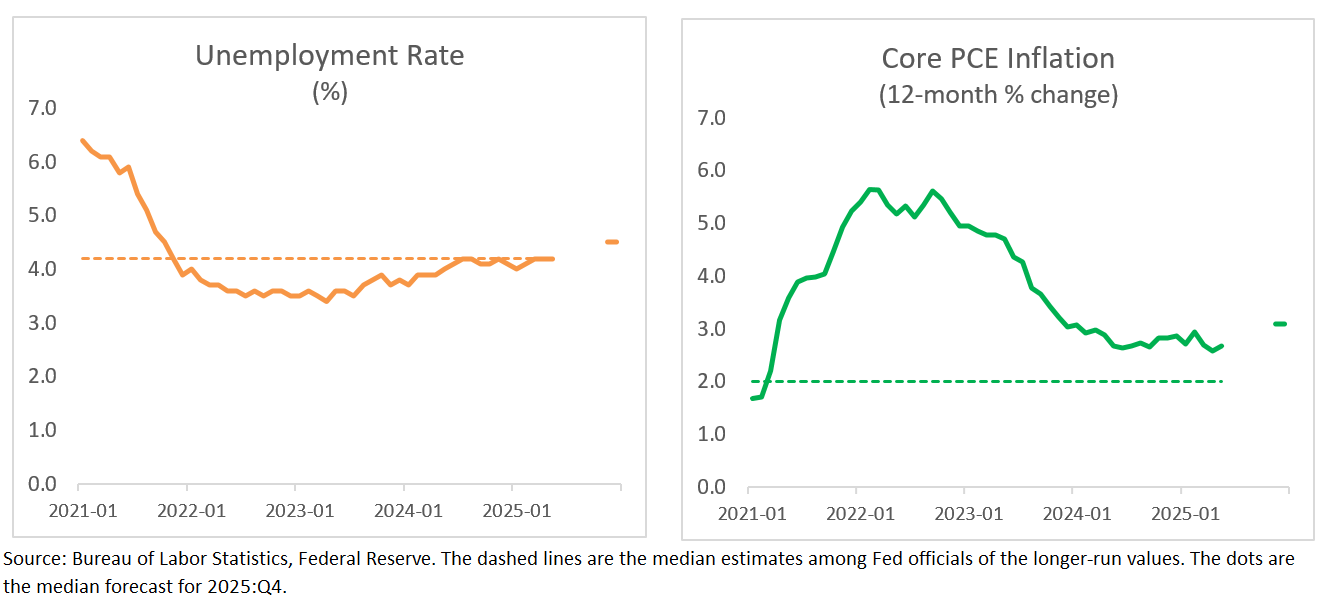

The unemployment rate and core PCE inflation have fluctuated within fairly narrow ranges over the past year, but the implications of these ranges differ markedly. The unemployment rate at 4.2% in May was in line with the median Fed official’s estimate of its longer-run level.

While the Fed does not have an official definition of maximum employment, the current unemployment rate is likely at or close to meeting that condition for most Fed officials. In contrast, core PCE inflation, at 2.7% in May, is somewhat above the Fed’s 2% target and has been above it since 2021.

The

reason that the federal funds rate is at 4.3%, which Fed Chair Powell has described as “modestly restrictive,” is to reduce demand and lower inflation to 2%.

Incoming data is also evaluated relative to the outlook. That’s the “learning” from the data. It’s the surprises that reshape the Fed’s thinking and could prompt a different policy response.

Nearly all Fed officials in June expected both unemployment and inflation to be higher by the end of the year. The median Fed official expects 4.5% unemployment in the fourth quarter and core PCE inflation of 3.1%. At that point, both unemployment and inflation would be somewhat off their mandate.

The median official viewed two cuts by the end of the year as appropriate. While Powell has cited the solid labor market as a justification for the current ‘wait-and-see’ approach, there is an expectation that the labor market will soften somewhat this year.

If unemployment rises to 4.3% in June, which is the consensus among professional forecasters, that would likely align with the Fed’s outlook of gradual weakening. If, instead, it jumped to 4.4% that would raise questions about the pace of weakening. However, that would be one month against a year of relative stability.

The Sahm rule recession indicator in that 4.4%-scenario would be 0.27, well below its 0.50 threshold. It would not trigger until the three-month average unemployment rate is 4.6%.

It’s very unusual for a single month of data to alter the forecast to the extent that it prompts a different policy response. Only two of the twelve voting members of the FOMC have made the case for a possible cut in July. Powell rightly said that July is neither ”off the table” nor “directly on the table,” but the bar in terms of the data would likely be high to bring the majority of the FOMC around to cutting this month.

It’s More Than Tariffs

The potential effect of tariffs on inflation and growth has been the central topic of economic debate for months. Still, the reductions in immigration that began last summer and accelerated under Trump could also be a stagflationary impulse that becomes evident this summer.

The significant decline in new immigration, the rise in deportations, and the loss of work authorization among some recent immigrants could weigh on labor supply and make it challenging to interpret the employment numbers. Weakness in job growth due to weakness in labor force growth, rather than weakness in labor demand, is a supply-side issue that the Fed typically does not try to address.

The number of new jobs necessary to maintain a steady unemployment rate, often referred to as the break-even rate, is expected to decline with reduced immigration. According to one of those analyses by Edelberg, Veuger, and Watson:

Slowing immigration will put significant downward pressure on growth in the labor force and employment. Potential employment growth, meaning employment growth when the labor market is operating sustainably at “full employment,” could be between 10,000 and 40,000 jobs a month in the second half of 2025 (down from 140,000 to 180,000 in 2024), and potential job growth could turn negative in the second half of Trump’s term.

With such a significant downshift in the break-even rate of job creation, it will be especially important to monitor changes in the unemployment rate as a gauge of labor demand. Assessing weakness in the labor market using payroll data alone will be challenging. The consensus forecast for payrolls is 110,000 in June.

A lower estimate, especially if it appears to be driven by industries with high shares of immigrant workers, such as construction and leisure and hospitality, would signal slower GDP growth, but not necessarily weaker demand for labor. When Powell says they are watching for signs of “unexpected weakness” in the labor market, it’s less demand for, not less supply of, workers.

Keep an Eye on the White House

The learning this summer is not only about the economic effects of policies, but it’s about the policies themselves. As a key example, we are fast approaching the July 9th deadline when the pause on the country-specific reciprocal tariffs ends. While few expect the country tariffs to revert to the higher levels announced on ‘Liberation Day,’ it is entirely possible that the effective tariff rate will end the summer higher than when it started.

President Trump’s announcement today that Vietnam will have a 20% tariff rate aligns with this pattern. The new rate is higher than the current 10%, but lower than the 46% announced in April, which had been paused.

The Fed has pointed to the level of tariffs as a factor in the persistence of inflation. Here is Powell after the June FOMC meeting (emphasis added):

Policy changes continue to evolve , and their effects on the economy remain uncertain. The effects of tariffs will depend, among other things, on their ultimate level . Expectations of that level, and thus of the related economic effects, reached a peak in April and have since declined. Even so, increases in tariffs this year are likely to push up prices and weigh on economic activity.

The effects on inflation could be short lived—reflecting a one-time shift in the price level. It is also possible that the inflationary effects could instead be more persistent. Avoiding that outcome will depend on the size of the tariff effects , on how long it takes for them to pass through fully into prices, and, ultimately, on keeping longer-term inflation expectations well anchored.

The larger the tariffs, the further inflation is likely to deviate from the 2% target, and the more likely it is to create a series of cost shocks across related industries. Businesses may need to spread large price level adjustments over time. So even if the tariff-induced inflation is transitory (and would recede without higher rates), the time it takes to return to 2% inflation might be unacceptably long for the Fed.

The evolution of both country and sectoral tariffs this summer will be crucial in assessing the stagflationary impulses in the economy. Higher tariff rates have the potential to put the Fed’s dual mandate in even more tension.

In Closing

A common refrain from the Fed is that “the current stance of monetary policy leaves us well positioned to respond in a timely way to potential economic developments.” The 4.3% federal funds rate appears to be modestly restrictive, and there’s plenty of room to cut if necessary. The Fed may be well-positioned to respond, but a ‘stagnation summer’ will make it challenging for the Fed to agree on the right response.

Original Post